Since it was founded in 1961, Amnesty International has been empowering people like you to take action for a better world. This is a snapshot of what you have made possible.

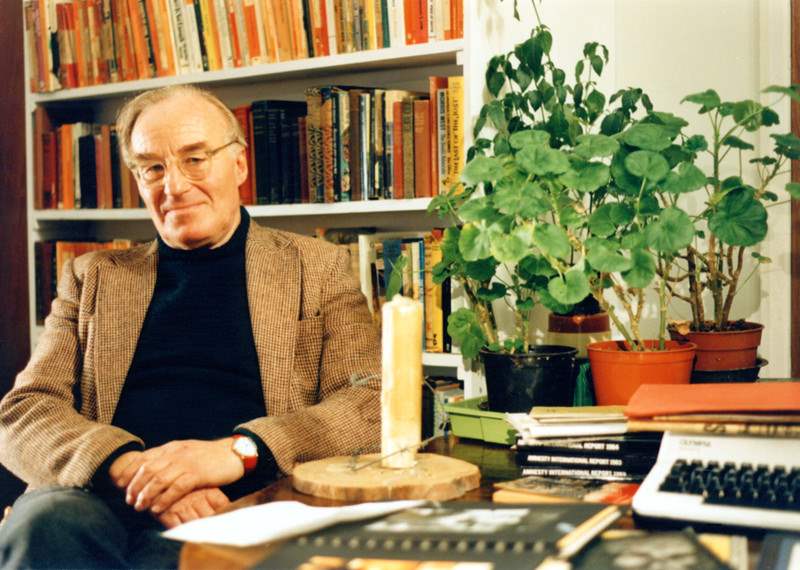

“Open your newspaper – any day of the week – and you will find a report from somewhere in the world of someone being imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government. The newspaper reader feels a sickening sense of impotence. Yet if these feelings of disgust all over the world could be united into common action, something effective could be done.”

– Peter Benenson

Amnesty International was founded in 1961 on the idea that together ordinary people can change the world. Today Amnesty is a worldwide movement for human rights, calling on the collective power of 10 million people, each one committed to fighting for justice, equality and freedom everywhere. From London to Santiago, Sydney to Kampala, people have come together to insist that the rights of each and every human are respected and protected.

Change has not happened overnight. It’s taken persistence and a belief in the power of humanity to make a difference. And the result? The release of tens of thousands of people imprisoned for their beliefs or their way of life. The end of the death penalty in dozens of countries. Previously untouchable leaders brought to account. Amended laws and changed lives.

How do we measure 60 years of collective action? It’s there in the accused who is given a fair trial; the prisoner saved from execution; or the detainee who is no longer tortured. It’s there in the activists freed to continue their defence of human rights; the school children learning about their rights in the classroom; or the families escorted safely home from refugee camps. And it’s there in the marginalized communities marching to demand an end to discrimination, the marginalised communities who defended their homes from destruction and the woman whose government finally outlaws the abuse she faces every day.

Sixty years on, we’re still battling for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. And we won’t stop until it’s achieved.

When I first lit the Amnesty candle, I had in mind the old Chinese proverb: ‘Better light a candle than curse the darkness’.

Peter Benenson

Humanity wins: Your impact over the last 60 years

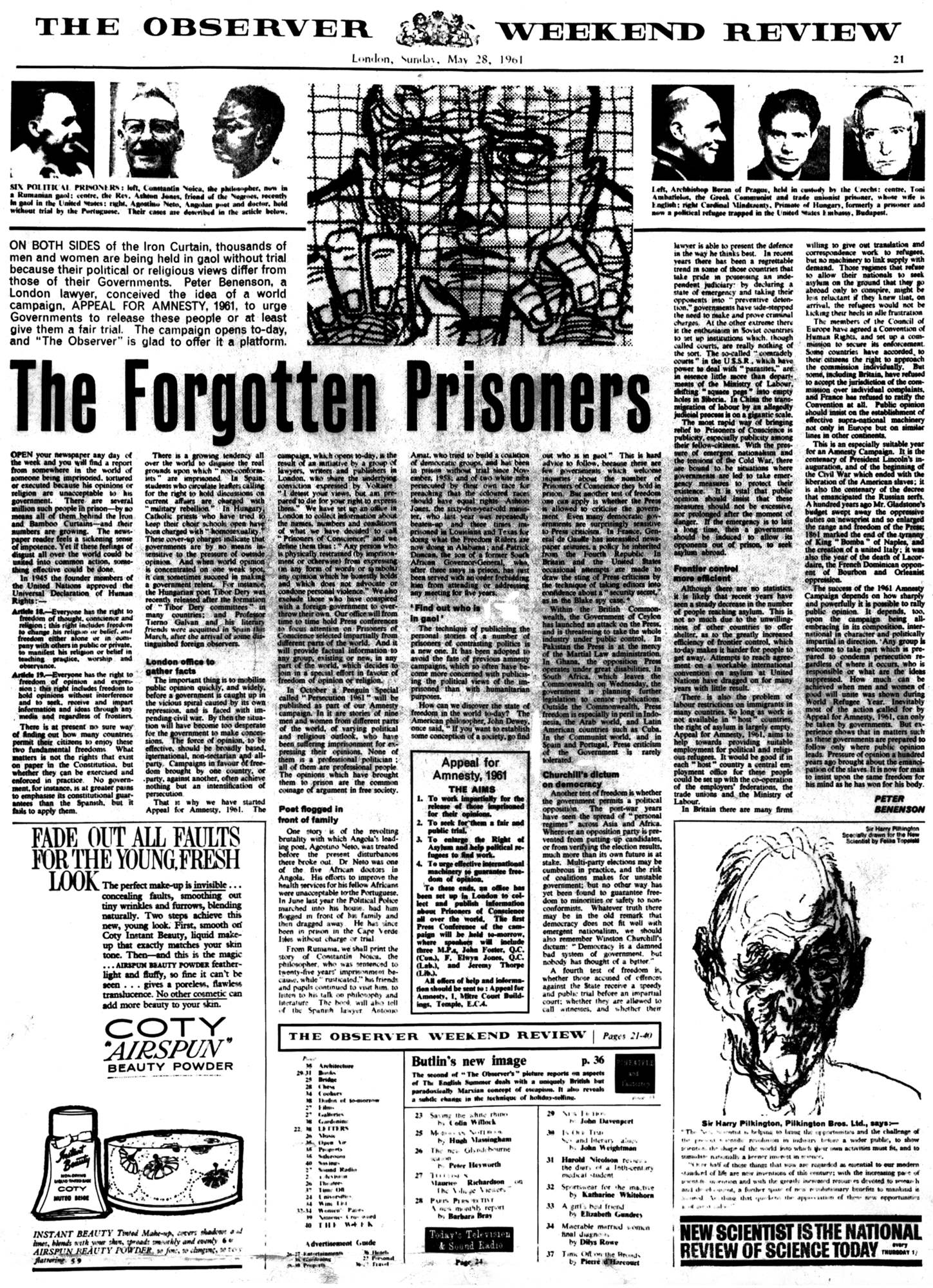

- After learning of two Portuguese students who were imprisoned for raising a toast to freedom in 1961, British lawyer Peter Benenson launches a worldwide campaign ‘Appeal for Amnesty 1961’. His appeal to free prisoners of conscience is reprinted in papers across the world and turns out to be the genesis of Amnesty International. By 1966, 1,000 prisoners have been released thanks to the tireless efforts of people, like you, who want to see a better world.

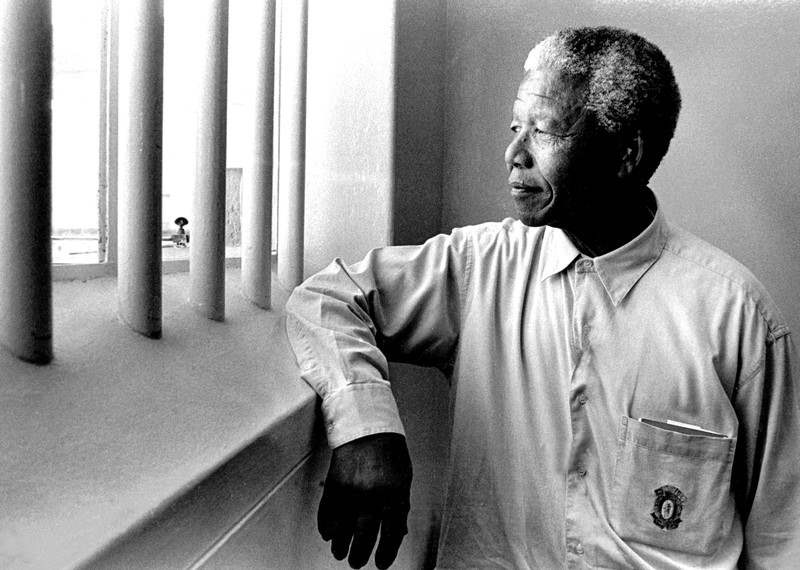

- In 1962, Amnesty sends a lawyer to observe Nelson Mandela’s trial in South Africa. Nelson Mandela wrote that “his mere presence, as well as the assistance he gave, were a source of tremendous inspiration and encouragement to us”.

- In 1973, Amnesty issues its first full Urgent Action, encouraging the public to act on behalf of Luiz Basilio Rossi, a Brazilian professor arrested for political reasons. Luiz would go on to attribute popular support for these appeals for improving his situation: “I knew that my case had become public, I knew they could no longer kill me. Then the pressure on me decreased and conditions improved.” Since then, Amnesty supporters across the world have campaigned on behalf of thousands of individuals, families and communities. In approximately one third of those cases, it results in positive change and even when it doesn’t, it lifts spirits and offers hope.

I received with much joy and emotion the beautiful cards and your encouraging messages of solidarity… Thank you very much.

Elmer Salvador Gutierrez Vasquez, Prisoner of Conscience, Peru

- In the 1970s, Chile’s new regime under General Augusto Pinochet agrees to admit a three-person Amnesty International mission to investigate allegations of massive human rights violations. More than 20 years later, Amnesty International is a party to legal proceedings that lead to Pinochet’s arrest in the UK for crimes committed in Chile. In 1979, Amnesty International publishes a list of 2,665 cases of people known to have “disappeared” in Argentina after the military coup by Jorge Rafael Videla, in an effort to help their friends and families hold those responsible to account. In the same decade, Amnesty International wins the Nobel Peace Prize for “having contributed to securing the ground for freedom, for justice, and thereby also for peace in the world” – a remarkable tribute to the hard work and determination of Amnesty supporters across the world.

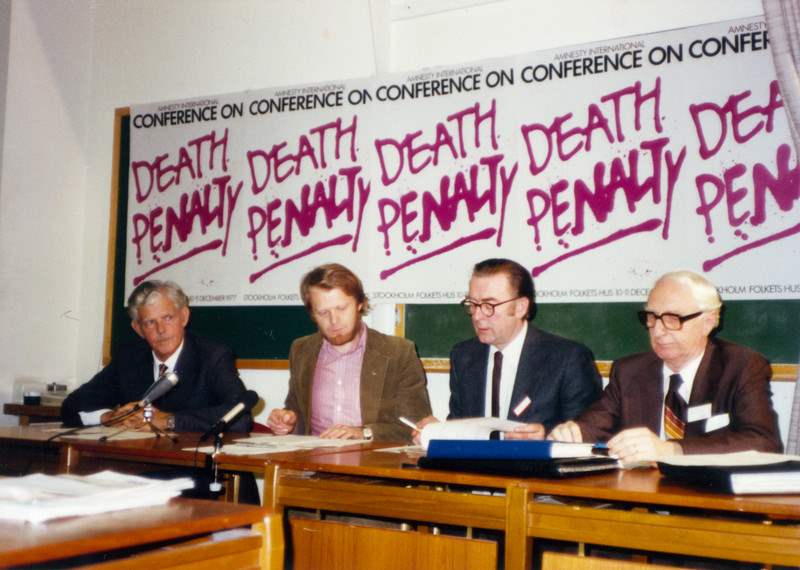

- When Amnesty and its supporters start the fight against the death penalty in 1977, only 16 countries had abolished the death penalty. Today, that number has risen to 108 – more than half the world’s countries. Since 2011, countries including Benin, Chad, Republic of Congo, Fiji, Guinea, Latvia, Madagascar, Mongolia, Nauru, Suriname have all abolished the death penalty for all crimes. Our success has been driven by the belief that the right to life is sacred. With your help, we will not stop until the whole world gets rid of this ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment, for good.

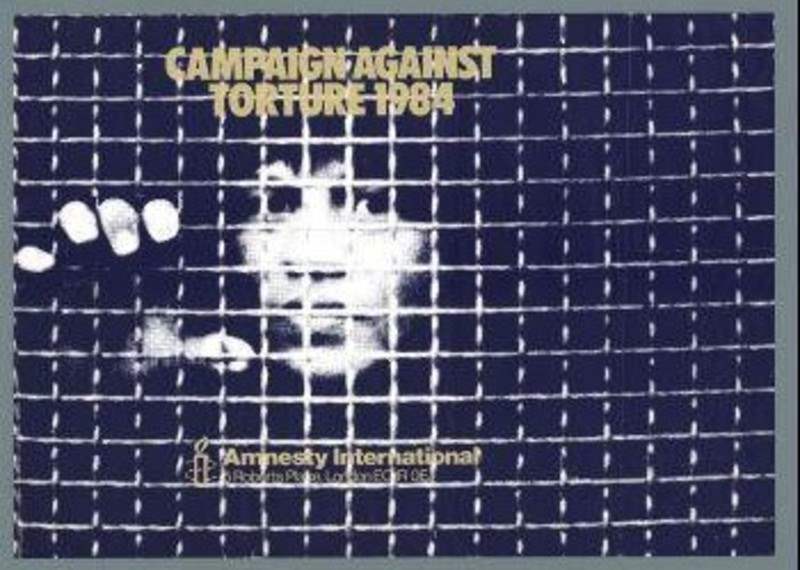

- n 1984, following tireless campaigning from Amnesty supporters, the UN General Assembly adopts the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. As a result, countries are now required in international law to take effective measures to prevent torture in territories they control and are forbidden from transferring people to any country where there is reason to believe they will be tortured.

- In the 1990s, Amnesty International reports on human rights abuses in Kuwait following the Iraqi invasion, making headlines across the world. Our teams also launch an action on torture and extrajudicial executions in Brazil and receive an immediate reaction from President Fernando Collor, who says “We cannot and will not again be a country cited as violent.” Amnesty International also draws global attention to the plight of 300,000 child soldiers, and joins forces with five other international NGOs to launch the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers.

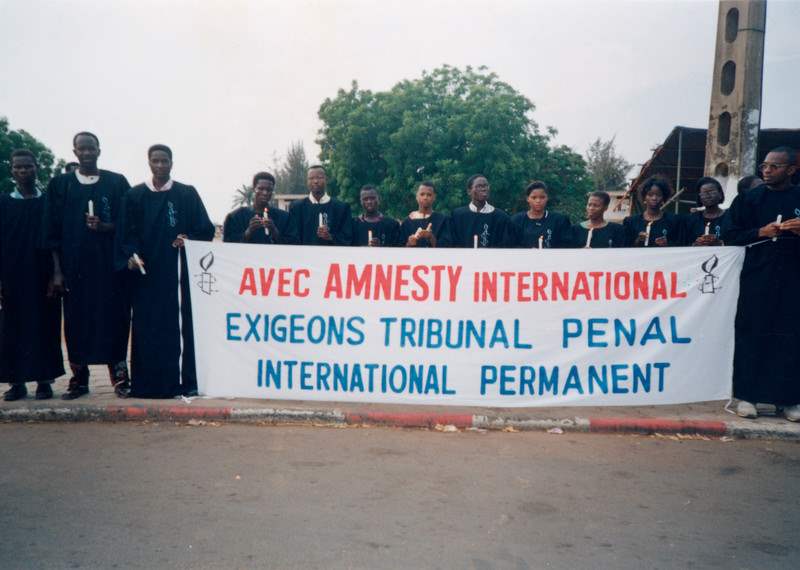

- In 2002, longstanding pressure from Amnesty supporters finally paves the way for the creation of an International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate and prosecute those, including political and leaders, leaders of armed groups and other high-ranking figures reasonably suspected of committing crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

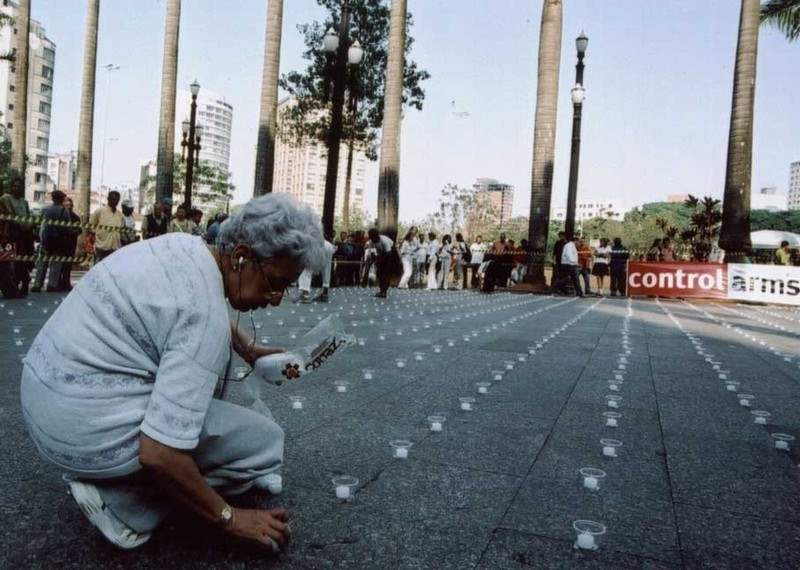

- After 20 years of pressure from Amnesty supporters and others, the global Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) comes into force in 2014, in a significant victory for humanity. The treaty is designed to stop the irresponsible flow of weapons that cause the deaths of millions and fuel conflict and widespread human rights abuse. This huge win would not have been possible without the amazing support of our donors, members and activists.

- The 2010s and 2020s are marked by an ever-growing number of human rights triumphs as activists intensify their demand for change. In 2010, for example, Amnesty International works with the Dongria Kondh, an indigenous community in Orissa, India, to prevent the Vedanta mining company from evicting them from their traditional land. Following these efforts, the Indian government rejects plans for a mine project on their land.

- In 2013, Papua New Guinea repeals the controversial Sorcery Act, which allowed for reduced sentences for murder in cases where an accusation of sorcery was made against the victim. This marked a breakthrough in the struggle to end violence against women in a country where accusations of sorcery have often been used as an excuse to beat, kill and torture women. There was further good news when the Family Protection Act (on domestic violence) was passed in the same year.

- In 2015, after years of pressure from Amnesty and its supporters, Shell’s Nigerian subsidiary announces a £55m settlement to 15,600 farmers and fishermen in Bodo, Nigeria, whose lives were devastated by two large Shell oil spills in 2008. It paves the way for future actions from other Nigerian communities which have borne the brunt of the company’s negligence. In 2021, the UK Supreme Court rules that two other Niger Delta communities affected by years of spills can sue the oil giant in a UK court.

- In 2015, the UN adopts stronger rules for the humane treatment of prisoners, following pressure from a coalition of NGOs including Amnesty International. The revised rules more fully respect prisoners’ human rights with a focus on rehabilitation; protection against torture; better access to health care; and restricting the use of punitive discipline, including solitary confinement.

- In 2015, Ireland becomes the first country in the world to introduce full civil marriage equality by a popular vote. “This [decision] sends a message to LGBTI people everywhere that they, their relationships and their families matter,” said Amnesty Ireland’s Executive Director, Colm O’Gorman. In 2019, Taiwan becomes the first in Asia to legalise same-sex marriage, following sustained campaigning on the issue.

- In a landmark ruling for international justice, former president of Chad Hissène Habré is sentenced to life on 30 May 2016 for crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture committed in Chad between 1982 and 1990. The prosecution relies on Amnesty reports dating from the 1980s, as well as the expert testimony of a former Amnesty staff member, among other evidence.

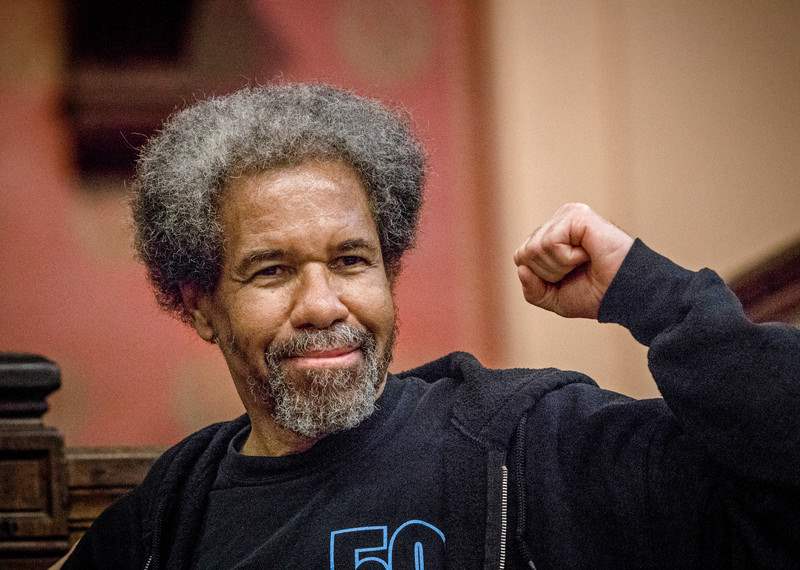

- Also in 2016, Albert Woodfox is finally released from prison in the USA following decades of pressure from Amnesty supporters. He had spent 43 years and 10 months in solitary confinement in a Louisiana state prison – believed to be the longest anyone has survived in solitary in the USA. “I can’t emphasise enough how important getting letters from people around the world is,” said Albert. “It gave me a sense of worth. It gave me strength – convinced me that what I was doing was right.”

- In 2017, the Kenya High Court blocks the government’s unilateral decision to shut Dadaab refugee camp, the world’s largest refugee camp. The ruling comes in response to a petition by two Kenyan human rights organizations, which was supported by Amnesty. Dadaab’s closure would have left more than 260,000 Somali refugees at risk of forced return to Somalia, a country wracked by armed conflict.

- In 2018, Teodora del Carmen Vasquez is released from prison after spending a decade behind bars in El Salvador after suffering a stillbirth, which led to her being accused and convicted of abortion, an illegal act in the country. She was released when a court reduced her outrageous 30-year prison sentence. From petitions to protests, Amnesty supporters had been campaigning for Teodora’s freedom since 2015.

- In 2018, a referendum in Ireland overturns the constitutional ban on abortions and marks a huge victory for women’s rights – arising from years of dedicated activism, including by Amnesty International. In 2020, Argentina finally legalizes abortion, a triumph for the women’s rights movement and Amnesty supporters who have been fighting for this for decades. It serves as an inspiration to other countries in the region and around the world to move towards recognizing access to safe, legal abortion.

- In 2018, a UK ruling finds that intelligence services’ use of private communications swept up in bulk breached human rights laws. This is the first time in its 15-year history that the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) has ruled against an intelligence agency. The landmark verdict proves that mass surveillance sharing on such an industrial scale is unlawful, and a violation of our rights to privacy and to free expression.

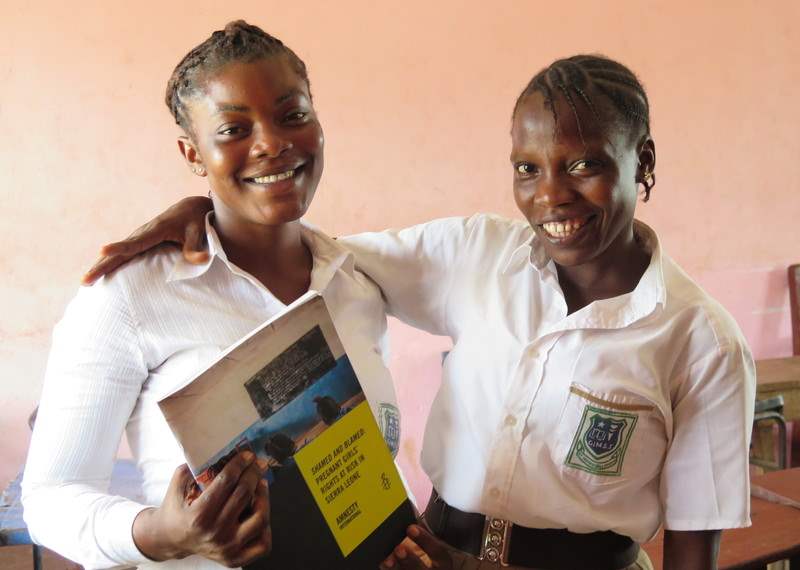

- In 2019, Sierra Leone lifts the ban on pregnant girls accessing education after it is found to be discriminatory. Amnesty had intervened in the case, drawing on its own research on the issue as well as relevant international law. The decision sent a strong message to other African countries either implementing or considering such bans.

- In 2019/20, changes to the law in Denmark, Sweden and Greece finally recognise that sex without consent is rape. This follows years of campaigning by women’s rights and survivors’ groups, and Amnesty’s Let’s Talk About Yes campaign. Spain also announces a bill to define rape as sex without consent, in line with international human rights standards.

While before I felt all hope had gone, the story changed when Amnesty came in. The messages I received overwhelmed me. I regained hope.

Moses Akatugba