Migration is one of the major livelihood strategies for the youths in Nepal. The International Labour Organization (ILO)[1] estimates that 400,000 young people enter the labour force every year in Nepal, out of which more than half leave for foreign employment mainly due to lack of employment opportunities within the country. As per the Department of Foreign Employment (DoFE)[2], over four million labour approvals were issued between 2008/2009 and 2018/2019. Most of the Nepali youths go to Malaysia and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries as contractual labourers taking up low-skilled or unskilled work. For many Nepali families, migration is more of a compulsion rather than a choice.

Labour migration has brought both opportunities and challenges to Nepal. The remittances generated from it have changed the socio-economic landscape of Nepal. It contributes to 23% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)[3], and in 2017/18, Nepal was enlisted in the list of top five countries[4] receiving the highest amount of remittance in proportion to GDP. Almost one in two (56%) of Nepali families receive remittances which have further increased the household budget and improved the livelihood of many Nepalis[5]. Remittance has helped to diversify income, improve health and education. It has also contributed to reducing poverty from 42% in 1995 /96 to 25.2%[6] in 2010 /11 to 16.6%[7] in 2017/18. In addition to obtaining economic remittances, migration has also helped gain social remittance in the form of knowledge, skills, experience, and social capital.

However, human and labour rights abuses of Nepalis who migrate abroad for work are widespread. Nepali migrant workers face several challenges during pre-departure, transit, and post-arrival in destination countries, and as returnees later in Nepal. The exploitation and abuse of aspirant migrant workers, especially during the recruitment process are widespread and yet unaddressed. Mostly the private recruitment agencies and their agents cheat and extort migrant workers with impunity. Amnesty International’s report “Turning People into Profits” states that migrant workers pay on an average NPR 137,000[8] to recruitment higher than an average income of a Nepali household. As a result, Nepali workers are forced to take a loan at staggering interest rates as high as 60% per annum to meet the recruitment costs thereby trapping them in a vicious cycle of debt and exploitation. In Nepal, migration is predominantly a male phenomenon. However, there has been a significant increment in the foreign labour migration of women. According to DoFE[9], in 2008 / 2009, the number of Nepali women leaving for foreign employment through the formal registration process was just 8,594 and this number significantly increased to over 20,982 in 2018 / 2019. However, this could be an underestimation as a huge number of women migrant workers are compelled to use irregular routes. Despite gvernment restrictions and societal barriers, foreign employment has made women independent economically and has contributed to their social empowerment as well.

The Nepal Government’s reform initiatives to minimize the cost of migration and protect the rights of migrant workers have not been adequately resourced, monitored, or enforced. The much-hyped “Free Visa Free Ticket” policy introduced in 2015 to control the exorbitant charging of recruitment fees remains limited only to paper. In 2017, Amnesty International[10] conducted a survey of 414 Nepali migrant workers in Malaysia which revealed that vast majority (88%) paid fees to recruitment agents for their jobs. In addition to the high recruitment fees, migrant workers are also deceived about the terms and working conditions in the destination countries which often leads them to situations of forced labour and debt bondage.

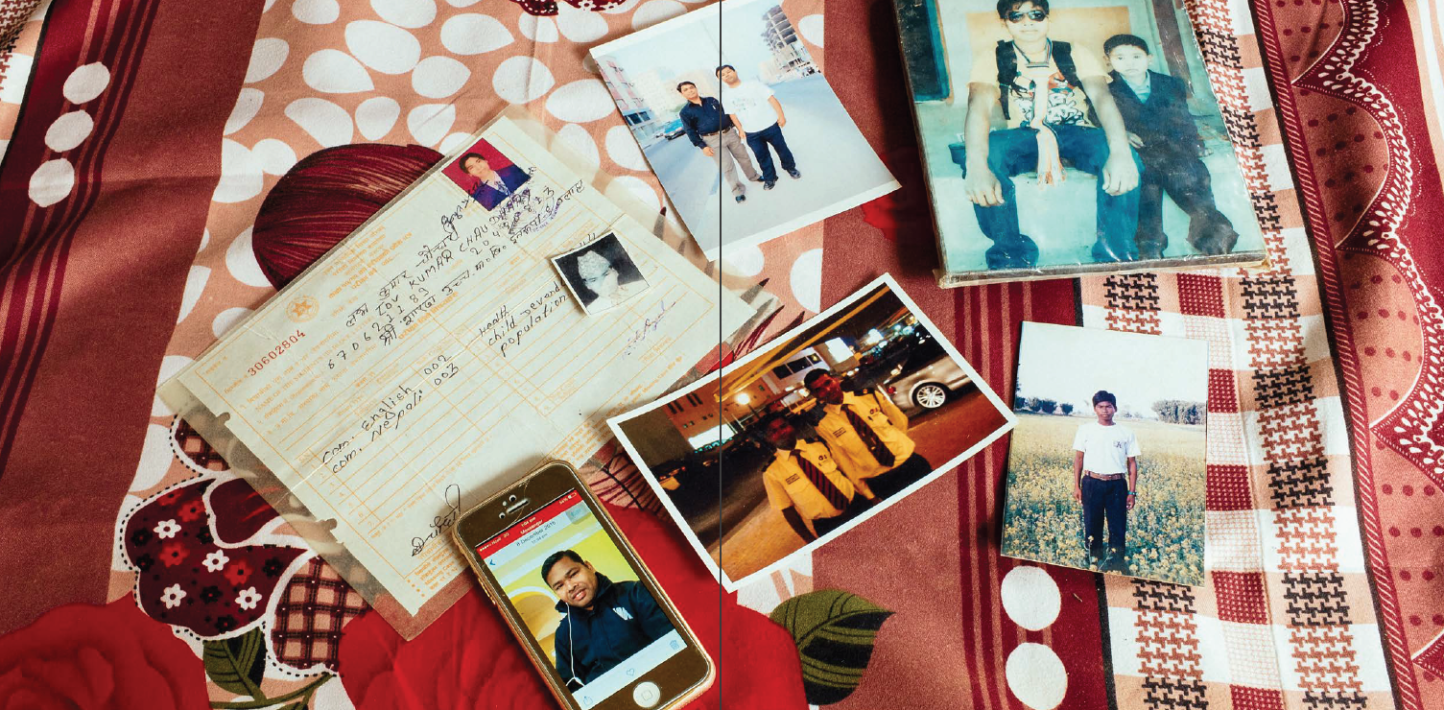

On the other hand, most migrant workers lack access to effective redressal mechanisms and are compelled to remain submissive to the violations and abuses they face. In destination countries, most Nepali workers are engaged in dirty, dangerous, and difficult jobs and face a range of exploitation and abuses. On average three dead bodies[11] of migrant workers arrive in Nepal daily despite the fact that the deceased were in good health with mandatory medical tests before entering the destination countries. The bereaved families are usually denied compensation as most of these deaths are categorized as «natural deaths» and vaguely defined cardiac arrests[12]. And there are hardly any investigations to determine the underlying causes of such deaths. Most of the discussions about labour migration have overlooked the role of families involved. They may have reaped the economic benefits of migration, however the social and emotional sacrifices they endure and new roles they need to adopt as a result of their family members being away from home have a huge impact. Social issues like broken relationships, accusations of adultery and impact on children and elderly have not been addressed adequately. On the flipside, taking on the role as the head of a family, women have also exercised a more active role in social and political spheres. Although foreign labour migration has improved the socio-economic conditions of the country and the families involved, migrant workers and their families face numerous hardships. Despite these challenges, labour migration remains popular and will continue to be one of the major sources of income for Nepali household and one of the highest contributors to the country’s GDP.

Ashmita Sapkota, Campaigns Coordinator at Amnesty International Nepal, contributed a chapter titled “Foreign Labor Migration: Opportunities and Challenges in Nepal” to the book “AU DE’SERT” published by Amnesty International France AU DE’SERT

[1] https://www.ilo.org/kathmandu/areasofwork/employment-promotion/lang–en/index.html

[2] https://nepalindata.com/media/resources/items/20/bMigration_Report_2020_English.pdf

[3] Nepal Rastriya Bank, 2022, https://www.nrb.org.np/contents/uploads/2022/05/FSR-202021.pdf

[4] World Bank, 2019, https://nepalindata.com/media/resources/items/20/bMigration_Report_2020_English.pdf

[5] Nepal Living Standard Survey- III, 2010/2011, https://time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/statistical_report_vol2.pdf

[6] Central Bureau of Statistics 2010/2011, https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2022/08/Neapl-In-Figures-2022.pdf[7] Ministry of Finance, Economic Survey