Despite the Right to Equality and Non-discrimination being enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the Constitution of Nepal, many people continue to be denied their fundamental right to acquire citizenship. Most of the people who have been unjustly denied their citizenships are people in poverty, from marginalised groups and communities, such as the Madheshis and LGBTIQ community, children with absent fathers, gender-based violence survivors, and others.

Although recently, with the amendment to the Citizenship Act , a passage has been paved for thousands of people who had been stateless in their own country to now become citizens, there are still numerous hurdles for thousands of others to obtain their right to citizenship.

To discuss what these Constitutional challenges are for the implementation of citizenship rights in Nepal, on August 14, Amnesty International Nepal, Women’s Rehabilitation Center (WOREC), and Forum for Women Law and Development (FWLD) jointly organised a program entitled ‘Statelessness: Consequences of GBV: Barrier for SDG Goal 5’. The event was organised as a part of Nepal Peoples Forum 2023.

The program was divided mainly into two sections: first was a presentation by WOREC on their findings of a research on how gender-based violence has obstructed women and LGBTIQ groups in acquiring their citizenship and denied their right to live a dignified life. This was followed by a panel discussion, composed of experts, policy makers, and politicians, where they discussed how existing discriminatory provisions pose a challenge in ensuring equal citizenship rights to all. The panel discussion was moderated by Sabin Shrestha, executive director of FWLD.

Amnesty International Nepal’s Chairperson Bipin Budhathoki started off the program with a short welcome note in which he stated that the existing challenges related to statelessness is multidimensional and that dismantling those existing barriers needed a targeted intervention.

“We must strive to build a world where statelessness based on gender does not exist and there is equality for all girls and women. For that, civil society organisations like WOREC, FWLD and AI Nepal need to work together with one voice,” said Budhathoki.

Following the welcome remark, Sulochana Khanal, program coordinator at WOREC, shared the findings of their research project ‘Statelessness: Consequences of GBV: Barrier for SDG Goal 5’.

According to the research, which was conducted during the period of January to February 2023, WOREC identified individuals without a citizenship certificate from 13 districts. A total of 136 people did not have citizenship certificate at the time of the survey, among which 81% were female.

“Among those who were denied citizenship, 21% were denied citizenship from their mother’s name. This was often due to fathers having citizenship by birth being untraceable, or lacking citizenship themselves,” said Sulochana Khanal. Another 10% were denied citizenship because of the type of citizenship their parents had. According to the report, approximately 10% of individuals cited not having the certificate because their parents or partner had citizenship by birth rather than descent.

“Our findings reflect how deeply ingrained gender roles are in Nepal. And all this is reflected on property ownership and inheritance rights as well. Such discriminatory provisions that further deepen intergenerational injustices not only disregard an individual’s identity but also rob them of their right to basic facilities, like buying a SIM card, opening a bank, accessing basic health care facilities, education, pensions, etc,” she said.

It is no secret that despite international commitments, current citizenship laws in Nepal are criticised for being gender discriminatory. Existing regulations hinder a woman’s ability to independently pass on their citizenship to their children. Despite legal clarifications and court rulings, inadequate implementation and gender biases have led to unjust denial of citizenship rights to many individuals, and addressing gender discriminatory laws and enhancing implementation are crucial for equitable citizenship rights in Nepal.

“Leave no one behind’ is the central promise of the 2030 agenda for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, but our country’s laws do not align with this promise; they instead go against achieving these goals,” said Renu Adhikari, Chairperson of Women’s Rehabilitation Center (WOREC), one of the panellists.

She went on to add that the notion that citizenship is not just divided in caste but also class and skin colour in Nepal. “A discriminatory attitude in our thinking is against the very spirit of the SDGs. What we need is a transformation in the mindset of people, only then will change come in the law. Denying a person their citizenship is not just a question of identity but of dignity and respect,” she said.

Dr. Brinda Pandey, leader, CPN UML, spoke on how the only way we can go forward and bring change is politically by including policy makers at every step of the way. “While we must raise the right questions, we must also know when to raise those questions. Coming together to discuss issues without the presence of someone who will take decisions in the lawmaking process will get us nowhere,” she said.

The panel also included Bimala Limbu, a resident of Morang, who shared her plight of being denied her citizenship and has no legal identity to call herself a Nepali citizen.

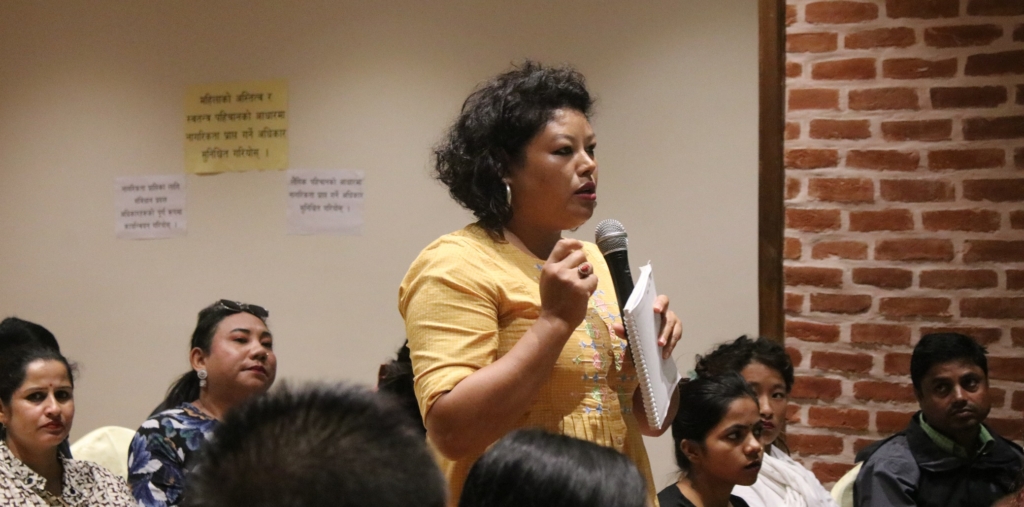

The floor was then open for questions. A range of questions were asked to the panellists, ranging from the issues that emerge when one must change one’s gender identity to issues of land ownership.

Following the discussion, a list of recommendations will be drafted which will then be sent to the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs and other necessary government entities.